The earliest museums did not look much like the ones we know today. They were repositories of stuff, Cabinets of Curiosity curated by enthusiastic collectors. When artist, naturalist, and scientist Charles Willson Peale what is widely recognized as America’s first museum in Philadelphia in 1786, he first filled it with his own paintings of George Washington and the bones of woolly mammoth. It was random, there was no narrative. Artifacts were preserved, but not interpreted.

In this self portrait, Charles Willson Peale pulls back a curtain on his museum, where artifacts are arrayed on shelves. (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

A lot has changed in the intervening decades (and centuries), and today museum exhibits do a lot more than display artifacts – they immerse visitors in narrative, pair artifacts with images, video, and audio, and feature innovative interactive experiences. The confluence of content and atmosphere mean that, more than ever, the best exhibits are developed not only by historians and curators, but by architects, designers, and programmers. Every aspect of exhibit design – from colors and fonts to lighting and layout – dictates how a visitor will experience and relate to the content, and it is critical that the design and content sync up.

This past fall I had the privilege of taking an Exhibition Design class through George Washington University’s Museum Studies program, which strengthened my conviction that public historians should become acclimated with the fundamentals of design so, at the very least, they can communicate with designers. And, as may be the case at smaller museums and historic sites, they will be prepared to take on the role of designer themselves.

Before and after photos of the First Ladies exhibit at the Smithsonian demonstrate how design can transform an exhibit. (Smithsonian Archives)

There is a lot to learn about design, from its principles to computer programs like AutoCAD, Photoshop, and InDesign that designers rely on heavily. To some extent, too, good design cannot be taught or even necessarily learned – as my graphic designer sister assures me, some people have a natural eye for it, others don’t, and that’s okay. It is not, by any means, something that public historians need, or, let’s be honest, even have the time, to become experts in, but again, I believe having a grasp on the basics is fundamentally important, and not too difficult. Here’s an brief overview.

Organizing Space

Designers are responsible for transforming a given space into an exhibit. This involves a lot more than put panels on walls and objects in cases. It means determining how visitors will move through the exhibit. Will they be guided through from beginning to end? How do you accomplish that? How do you signal to visitors how to move? One prominent example of such an exhibit is the main gallery at the United States Holocaust Museum and Memorial here in Washington, D.C. Other exhibits have an open flow, visitors can move freely from one area to the next. How an exhibit is laid out will have a major bearing on the organization and order of the content.

Color and Texture

The colors, textures, graphics, and materials used to fabricate an exhibit go a long way in setting the environmental mood and thus a visitor’s experience. Cool colors often create a more modern atmosphere, while warm colors tend to feel more historical or earthy. Texture adds a different layer of sensation, and can further immerse a visitor in the experience. The Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum makes good use of texture, including walls made of rough rock that give the visitor the feeling of entering a mine.

Exhibit Labels

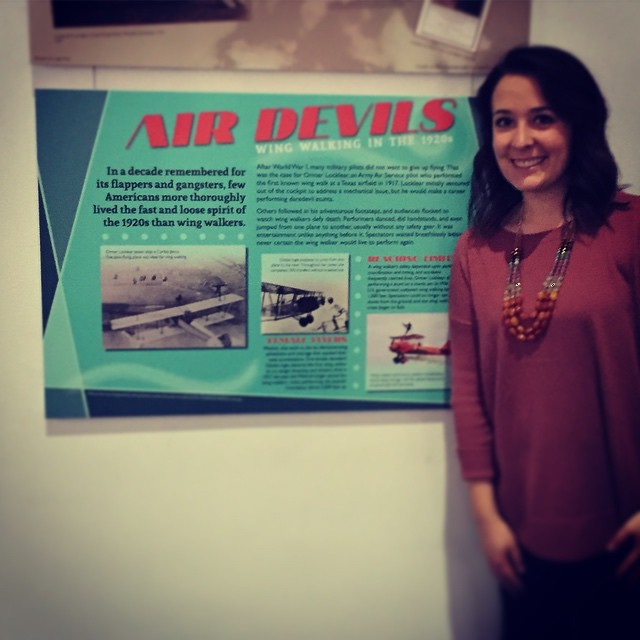

Exhibit labels are important not only because they convey content but because, if done poorly, a visitor will not take the time to read them. Historians need to work with designers to make sure their labels are the right length, while designers select the typeface, size, and placement of the text. The text must be readable at appropriate distances, and also for visitors with vision impairments, so it cannot be too small (or too big), or employ a font that it is difficult to read. The color of the font must be appropriate for the background of the panel, so there is enough contrast and visibility. The designer must also establish hierarchy, so visitors can distinguish titles from labels and captions. It should ensure that, even if a visitor only skims parts of panels, they easily be able to identify what is most important to read. Hierarchy can be seen in the photograph of the poster I designed below – the title is prominent, as is the lead that is meant to hook the reader. The main text is larger than the sub-topic text, which is larger than the image captions.

Lighting

The way an exhibit is illuminated can also has significant bearing on visitor experiences. Dark spaces convey a serious mood, giving content a certain gravitas, while open, light spaces do just the opposite. Records of Rights at the National Archives is a good example of an exhibit with appropriately low lighting. Of course, mood is not the only reason for lighting decisions. Lighting designers must also work with conservators to ensure that objects are not exposed to damaging amounts of light, another reason for the low lights on delicate documents at the National Archives.

This is just a small glimpse at the important work that designers do in bringing history to the public, but hopefully a helpful one. For more information I would recommend Kathleen McLean’s excellent Planning for People in Museum Exhibitions.

The poster I designed for my Exhibition Design class is currently on display on at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.